In the weeks since my website was launched several people have asked about the story behind my coal country photos. Most of these pictures were made between 1985-1987.

At the time I was working as an editor for a church organization. I was writing and photographing for publication already but wanted to be a full-fledged photojournalist, and was looking for opportunities to hone my skill any way possible. Having lived in Kentucky as a child I had a long-time interest in Appalachia and the history of coal mining. I had heard it was hard, even dangerous, to approach people in some of the more isolated parts of Appalachia. However (even as a Marylander) I felt my childhood roots and a degree of empathy might be of help in tackling the subject. Since Kentucky was just a day’s drive away I decided to make this project a self-taught course in Photojournalism 101. Little did I realize how deeply this decision would affect my life.

I scrimped up enough money to buy a brick of Kodachrome film, got a long weekend and made my first trip to Harlan County, Kentucky. I knew nothing about the place and it took a few trips for me to gain the confidence I needed to start working in depth. It wasn’t easy to approach people in some of the coal camps and remote hollers where I put myself. I’m a reclusive person too, and it took all the courage I had to initiate contact in those places. But the relationships that developed over time made the effort worthwhile, and the education I got from this project had more to do with life and the common bond of humanity than photojournalism.

In 1988 I wrote an essay, “Living on the Edge”, about a family I had become acquainted with and my observations as an outsider visiting coal country, and submitted it with some of my photos to Washington Post Magazine. To my surprise I was invited by then-editor Stephen Petranek (later to become senior editor at Life Magazine) to come discuss the story with him. He liked it and my photos well enough to spend nearly two hours explaining to me why they couldn’t be used in the Post magazine (too far from the Washington region to have enough relevance to readers).

Although they were never published, the photos I had taken in coal country up to that time became the primary reason I was hired by a development and relief agency in 1986 to document development projects in east Africa, and later in Central America. That work, in turn, was responsible for opening other doors for me, so the indirect benefit of doing this work would be hard to overstate. Not least of all it showed me my own ability, and gave me the confidence to think of myself as a photojournalist.

Several years later I happened to meet Betty Satterwhite, chief researcher for Time Magazine, at a friend’s party. In exchanging notes about our work I mentioned that I’d done a piece on Appalachia with photos that never had been published, and she said she’d like to read it. I sent her a copy of “Living on the Edge” with a cover letter. She mailed it back back a few weeks later with no letter of acknowledgment. A few months later Time Magazine came out with a cover story on the travails of coal country that hit every major point my essay had made.

It was gratifying to see a light shone on the subject, and feel my own work might have had a little something to do with Time’s decision to cover it. Of course it would have made me even happier to have a part in their story, even if only one of my photos had been used. But I wasn’t asked to participate, and by then understood publishers tend to go with resources and talent they already know.

Later I was privileged to shoot several assignments for Washington Post magazine but that’s another story. “Living on the Edge” is linked below this post. For those who read it, the Tollivers are pictured near the beginning of my “Coal Country” gallery, as is John Blevins – you’ll probably identify them easily after reading the essay.

The heroine of my novel “The Redemption of Valerie Tolliver” (link below for the ebook) was named as a tribute to the Tollivers I met in Harlan County. Valerie is a fictional character, but she and the portion of the novel that unfolds in Kentucky were informed in large part by the time I spent in eastern Kentucky, coming to know the lives, hardships and stamina of these iconic Americans. They are the stuff of folklore but they also are contemporaries, living very much in the present we all share. I hope everyone reading this will download my novel and enjoy the ride a little more for having seen these photos.

Links: Living on the Edge, The Redemption of Valerie Tolliver

Back to Coal Country gallery

__________________________

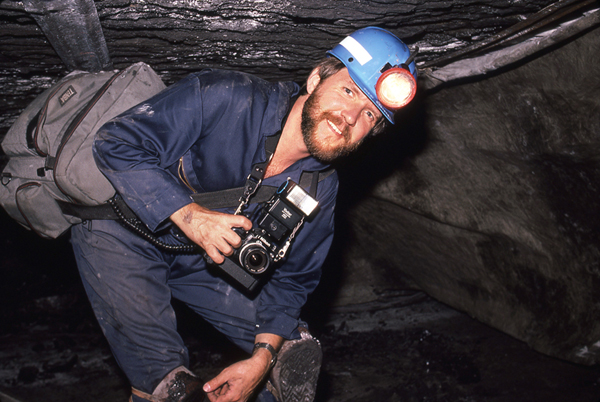

The photo below from 1986 only hints at how hard it was to shoot pictures in a coal mine. For starters, you can’t stand up – the height of most deep mines is just enough for working on your knees. And except for headlamps on helmets and machinery, it’s pitch black. Every mining photo I made had to be prefocused using a flashlight. Then there was the helmet, which had a visor that prevented me from putting a camera with an attached flash up to my face. So the helmet had to be off for most of the actual photography, a major safety concern. Last but far from least, I was in a working environment and needed to stay out of the way. The miners were great sports; they held flashlights and reflectors to help me make the best of a hard situation. One day one of them grabbed my other camera and turned it back to fire at me – a little bit of justice for which I’m grateful now.

Dennis

Great picture and description of mine work – hard to know how they can tolerate those conditions for so much time. You are really an authentic photojournalist taking your quest for truth to the challenging realities of life in one of our societies most difficult jobs.

Keep on doing good work!

Robert